In December, a diverse group of experts got together to chew over how to collectively improve food composition data.

This week, HASP Co-Director Prof Michelle Morris joined Dr Maria Tracker, Research Leader at the Quadram Institute, to share learnings from the event in a joint blog for the Quadram Institute.

What was the Food Composition Roundtable event?

It is not often that a range of stakeholders with a shared passion for a better food composition database get together with a sole purpose to think about food composition data!

On Friday 12th December, 27 of us convened at Caxton house in London, in an event hosted by the Quadram Institute.

With delegates from different parts of industry, government, academia, and the third sector we had wide representation, expertise, experience and passion for food composition data.

We spent some time setting the scene before discussing the value, opportunities and risks in doing things differently. Opportunities were highlighted through short talks and after a coffee break we reconvened into group activities before reporting back and thinking about next steps.

Where are we now?

Food composition data currently exists in silos, in a fragmented way and joining these diverse sources together is challenging and sometimes impossible.

We have the McCance and Widdowson’s Composition of Foods database (CoFID), which provides high quality composition data with over 3000 generic foods, each with detailed information on over 280 nutrients, including macro- and micronutrients. These data are open access and freely downloadable online.

CoFID aims to give an in-depth nutritional composition for foods that represent what people in the UK eat. However, with tens of thousands of foods on the supermarket shelves, the coverage of CoFID is limited.

Commercial data sources on food composition exist to fill these gaps and provide nutrient information on individual branded products that we typically buy. These all contain the eight nutrients that we can see on the back of a packet in supermarkets, mandated by labelling legislation, and micronutrient information for fortified products (micronutrients added).

Such primary data from labels can then be extended to fill in missing micronutrient values based on, primarily, CoFID, and to categorise foods, but without a standardisation framework.

Examples of primary and extended data sources include: NIQ Brandbank, Syndigo and myfood24, Nutritics. However, these commercial sources exist behind a paywall which means that not everyone can access them with costs often prohibitive. These companies may additionally have ingredient data, packaging information and derived metrics like Nutrient Profile Model (NPM) scores and High in Fat, Salt and Sugar (HFSS) status that are generated by teams within that company. This means that there is no single source of truth for food composition data in the UK.

Different versions of food composition data mean that food composition data is not standardised. This can become a problem when being used to implement policy as it means that different versions of the data are being used by stakeholders during implementation and then in turn a potentially different version for evaluation and for enforcement. Policy enforcement is devolved to local authorities with small budgets who potentially can’t access the detailed commercial data at all.

What is needed to fix this problem?

There is always a cost to doing things differently. However, the cost of not making a change is also expensive. As things stand every business that uses food composition data has to develop their own bespoke solution and approach which is expensive and when multiplied across the food industry and to other sectors requiring this data (national and local government, charities and research institutions), sums to tens of millions very quickly and potentially billions in the medium term.

We need to work more efficiently.

Bring together high-quality data when they exist and step-up the quality of other data when they don’t. The former requires agreeing a common ‘language’ for data connectivity.

In the data science world this is termed ‘interoperability’’ and consists of well-defined ontologies, A set of concepts and categories in a subject area that shows their properties and the relations between them data models and terminologies for foods and their related food composition data, which is currently lacking or not up to par. The latter requires data standardisation frameworks agreed and implemented either at source (when data are captured from labels or generated through lab analysis) or when the data are transformed for policy implementation.

Finally, we need primary data, underpinning further data transformations, to be current and their updates to target the gaps that will amplify and raise the quality of the extended food composition data for all.

What did our roundtable event cover?

Judith Batchelar OBE welcomed delegates to Caxton house and set out our mission. Dr Maria Traka took over setting the scene with detailed examples from McCance and Widdowson’s CoFID and beyond.

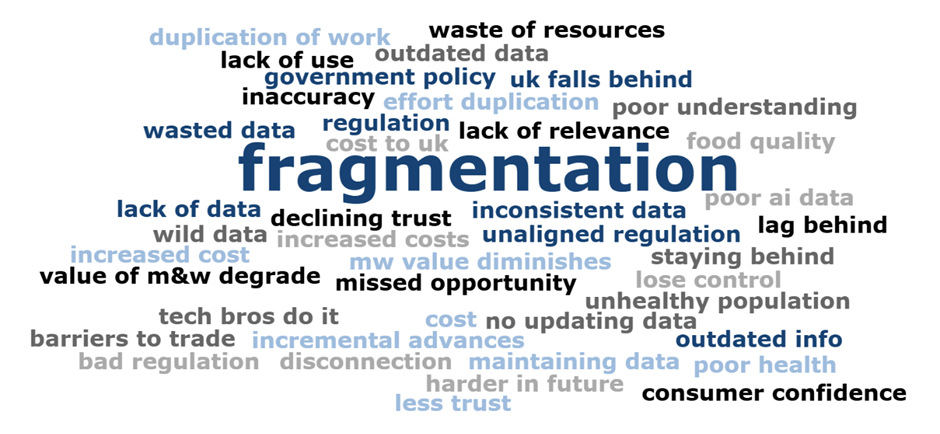

Prof Michelle Morris ran an interactive session to explore the perceived value, opportunities and risks in doing things differently with questions such as:

What do you see at the main opportunities for a centralised food composition database? And what are the risks of doing nothing, maintaining status quo? The word clouds below summarise the responses.

A series of short talks highlighting opportunities followed from:

- Ann Godfrey (GS1) talking about QR codes, the Digital Product Passport and the future potential of carrying substantial nutritional information on product labels

- Matthew Gilmour (Quadram) talking about the Food-Microbiology Intelligence Network and a paradigm for sharing sensitive microbiology safety data for public/private benefit

- Michelle Morris (University of Leeds) with an example using supermarket sales data from four major retailers to evaluate the impact of national legislation

Fuelled by tea and coffee, we finished the day with a series of working groups discussing:

- Database content, including quality and scope

- Technical requirements from a data and digital perspective

- Membership models, including the financial/business model

We closed out the morning agreeing some key next steps, before sharing lunch. We are now working on a full report form the meeting, but for now we will leave you with our key take home messages.

Take home messages

- There is a shared will to work differently to improve the quality, coverage, consistency and access to world leading food composition data in the UK

- There is a cost to maintaining the status quo and to changing the way we work – but the costs from changing will improve data quality and benefit all stakeholders considerably in the longer term.

- We need more primary data, we need standardisation of primary data transformation, and we need better access to the data

- Strong leadership and governance are essential

- Clear uses cases are essential

- We can learn from other sectors – this has been achieved before

- With more comprehensive data consumers can make more informed choices and debunk misinformation (e.g. via a QR code on foods)

- We will continue this journey together

This article was originally published by the Quadram Institute.