Lizzy McHugh – Impact and Partnerships Manager

With further restriction on foods high in fat salt and sugar coming into force this week, our Impact and Partnerships Manager Lizzy McHugh discusses the regulations and some of the data challenges we face when it comes to implementation, enforcement and evaluation.

One of the greatest challenges we face in the UK is the huge impact of poor diet at a population level. The latest National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) that was published earlier this year showed that 85% of children and adults are consuming over the recommended amount of sugar and fewer than one in five adults are consuming the recommended ‘5 A Day’ portions of fruit and veg.

Foods high in fat, salt & sugar (HFSS) make up a much higher proportion of our diet than they should and in the past thirty years rates of people living with obesity have doubled1. The economic cost of this unhealthy food system was estimated by the Food Farming and Countryside Commission to be £268 billion when taking into account the healthcare costs, social care and productivity losses.

The Food Policy Landscape

There has been a plethora of policies attempting to improve diet over the last 30 years, but historically they have had little impact on rates of obesity or health inequalities2.

Whilst recently there has been much media and industry attention on the rollout of GLP-1 weight loss medications as a treatment tool, there is still a need to tackle the systemic issues affecting what we eat, particularly as costs of medications are rising.

Currently much of the focus for preventative legislation is around food that is defined as high in fat salt and sugar (HFSS).

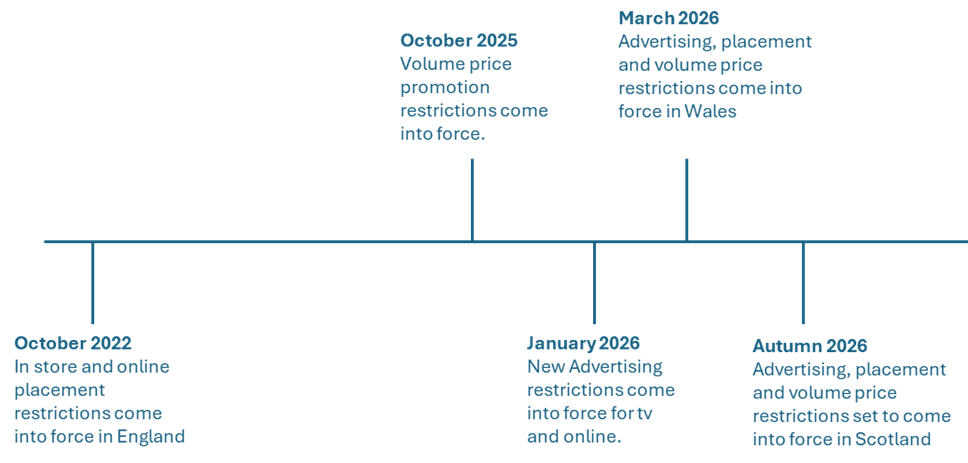

In England in October 2022 the previous government introduced restrictions on these products as part of their Childhood Obesity strategy.

The current Labour government also recently published their 10 Year Health Plan in which they laid out potential preventative methods to combat poor diet and obesity, including work on school food standards, planning restrictions on certain types of food businesses, restoring the value of Healthy Start vouchers and expanding free school meals.

More industry targeted policies included strengthening the existing Soft Drinks Industry levy, commitments to reducing junk food advertising, updating the Nutrient Profiling Model and banning the sale of energy drinks to under 16s. They also committed to introducing mandatory reporting on healthy food sales by the end of parliament with the support of their Food Strategy Advisory Board, with a view to bringing in targets.

Identifying products as high in fat, salt and sugar can be challenging

There is no definitive way to classify a food as healthy or not, but the most used mechanism in the UK for policy and industry is the Nutrient Profiling Model.

This was developed in 2004 by the Food Standards Agency and has been used historically to define whether food products could be advertised to children.

The model considers both positive and more negative nutritive components in food and gives them a score to determine if they are “HFSS” or not.

However, understanding if a product meets the criteria for legislation can be complicated.

Our Nutrient Profile Model Calculator, developed by Dr Victoria Jenneson, offers a quick and consistent way to assess whether a product may be subject to the HFSS legislation.

The calculator enables users to easily calculate a product’s NPM score – without requiring prior expertise in nutrition or food regulations.

In-store and online restrictions

The October 2022 legislation introduced restrictions on where HFSS foods could be displayed within supermarkets and online (for example, not on the end of aisle or near entrances, or the equivalent pages online).

Research led by Professor Michelle Morris as part of the DIO food project analysed in-store sales data from retailers (Tesco, ASDA, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons) to understand what happened to HFSS sales before and after the introduction of these restrictions.

The research estimated that 2 million fewer in-scope HFSS items were sold per day across all eligible supermarkets in England. Importantly, using the Priority Places for Food Index, it was found that the same level of reduction was seen across all types of neighbourhoods.

However, whilst these results are promising, the researchers suggest that there could be even more progress if systems for reporting, enforcement and evaluation were improved. No notifications, warnings or fines were reported by any of the surveyed retailers.

The research highlighted challenges around accessing the data needed to enforce or evaluate legislation based on NPM scores, as this information is not available on the back of pack nutrition label or openly accessible elsewhere. The researchers are calling for a centrally-managed open access, regularly updated food composition database3.

As of 1st October this year, there are also restrictions on these products being sold as part of volume-based price promotions. With these promotions, customers are encouraged to purchase a higher volume of products to get a saving (think 3 for 2 offers) which can lead to excess purchasing of less healthy foods. This does not affect price reductions such as fifty percent off. These restrictions were originally intended to come into force at the same time as the placement restrictions; but were delayed with the government citing the cost of living crisis.

The governments of both Scotland and Wales have committed to introducing the same restrictions in those devolved nations, with Northern Ireland likely to introduce something similar.

Advertising HFSS products

Online and Broadcast Media

In 2007, Ofcom, the media and communications regulator, introduced rules to reduce the exposure of children to HFSS products through TV advertising, with rules on not advertising HFSS products on programmes aimed primarily at children.

From January 2026 there will be further restrictions on which products can be advertised online with the hope that industry will voluntarily adopt these rules from this October, the original intended implementation date. For TV and streaming services, there will be a 9pm watershed on showing adverts for those products defined as HFSS. And online there is a total ban on paid for advertising of HFSS products, including paid-for influencer marketing.

But the restrictions will not cover adverts that just refer to the brand and don’t contain the actual products, a move that has not been welcomed by many NGO’s.

The Committee of Advertising Practice has released another consultation on the regulations following an update from the Government to confirm exactly what this means in practice and how the Advertising Agency will police this once the regulations are in place.

Unless there is a change to existing data systems, the challenges around lack of available data for enforcement and evaluation that have existed for the placement restrictions will continue.

This reiterates the need for an open, regularly-updated food composition database, which includes the HFSS-related data fields, to enable accurate and efficient implementation, enforcement and evaluation to ensure legislations have the best possible chance of achieving their intended outcomes.

Physical Advertising

The advertising legislation does not cover the likes of physical advertising, such as bus stops and billboards. However, some local authorities are taking action and introducing restrictions at a more local level, despite pushback from advertising bodies.

Transport for London, who were first to take action in 2019, found a ban on HFSS advertisements on their network have reduced the amount of calories purchased from HFSS products by 1000 per week per household4.

Recent research, from Dr Victoria Jenneson et al, has highlighted how the amount and type of outdoor advertisements can vary by place.

The project highlights disparities in how physical advertising of HFSS foods is distributed with more physical HFSS adverts found in deprived areas within Leeds, suggesting further regulation on physical advertising could go some way to reducing these inequalities5.

Thinking ahead

Making changes to the food system is complex. Findings from the DIO food team highlight that although current mechanisms are a “good first step”, there are improvements that could be made to increase the positive impact.

Having the right data available at all points, for implementation, enforcement and evaluation is critical to understanding and ensuring that these policies, which depend on data, are having the best possible impact.

Further research and evaluation will be needed to determine if these mechanisms can continue to drive positive outcomes.

Useful Information

Use the Nutrient Profile Model Calculator.

Explore the Priority Places for Food Index.

Speak to Lizzy find out more about working with HASP.

References

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. ‘Risk Factors Driving the Global Burden of Disease’ 2024. https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/library/risk-factors-driving-globalburden-disease

- Theis, D.R.Z. & White, M. (2021) ‘Is Obesity Policy in England Fit for Purpose? Analysis of Government Strategies and Policies, 1992–2020’, The Milbank Quarterly, 99(1), pp. 126–170. [Accessed 18 Sep. 2025].

- Kininmonth, A. R., Stone, R. A., Jenneson, V., Ennis, E., Naisbitt, R., Johnstone, A., … Fildes, A. (2025, March 26). “It was a force for good but…”: a mixed-methods evaluation of the implementation of the High in Fat, Sugar and Salt (HFSS) legislation in England.

- Yau A, Berger N, Law C, Cornelsen L, Greener R, et al. (2022) Changes in household food and drink purchases following restrictions on the advertisement of high fat, salt, and sugar products across the Transport for London network: A controlled interrupted time series analysis. PLOS Medicine 19(2).

- Jenneson, V.L. et al. (2025) ‘MAAP – Mapping Advertising Assets Project: A cross-sectional analysis of food-related outdoor advertising and the relationship with deprivation in Leeds, UK’, Public Health Nutrition, pp. 1–33.

- Kininmonth, A. R., Stone, R.A., Jenneson, V., Naisbitt, R., Wilkins, E.L., Van, D.T.T., Johnstone, A., & Fildes, A., Morris, M. A. (2025). Restricting less healthy foods in retail environments: Evidence-based recommendations for policy impact.

- Jenneson, V., Kininmonth, A. R., Wilkins, E., Chukwu, I., Eselebor, O., Pontin, F., … Morris, M. (2025, August 22). Did High in Fat, Sugar, and Salt (HFSS) product placement legislation in England lead to reduced HFSS purchases? An interrupted time series analysis.