We’re a nation of pet lovers. And while we might debate cats vs. dogs or guinea pigs vs. bearded dragons, most of us agree on one thing: pets offer invaluable companionship and a real boost to our physical and emotional well‑being.

But with rising pet care costs and the emergence of ‘veterinary deserts’ in some areas, we face the risk of pet ownership becoming out of reach for some communities.

Providing care for pets

Choosing to own a pet is a big decision for any household. This is especially emphasised by campaigns by animal charities to remind households that a “Dog is for life, not just for Christmas”.

In addition to the requirements that pet ownership has on a household’s time, there are also the financial costs. These costs include the purchase of the pet, food, equipment, toys and of the most concern for this study, veterinary care.

Various issues with the veterinary care sector in the United Kingdom have recently been highlighted in the media. The main issue is the high cost of care and the associated high price of pet insurance. The chart below shows the recent trends in an all items price inflation measure and an equivalent measure for veterinary and pet related services. For the past two and a half years the pet services inflation has far exceeded that for all items.

Financial barriers that result in the failure to obtain care for pets is not only distressing for the owners and their pets, but also has the potential to increase the communicable disease burden in the general pet population.

Many believe that a main driver for these increased costs is a consolidation of veterinary practices into just six main operators. These concerns prompted the Competition and Markets Authority in the UK to launch an inquiry into the veterinary care sector and its findings were published in late 2025.

Whilst many of the recommendations are laudable, they only begin to be effective if pet owners have a realistic choice in which veterinary practice they can take their pet to. If such market-based competition genuinely exists then this should help to reduce costs. To help with this, the study we describe here provides a geographical assessment of where these options for pet owners in England and Wales are good, and where they are poor.

The neighbourhoods where we identify relatively poor access to veterinary care begin to signify the possible existence of ‘veterinary deserts’, where pet owners have little choice in which practice to use. The details of the study are published in our recent article in the Animal Welfare journal.

How we measure access to veterinary practices

To provide these measures of accessibility to veterinary practices a variant of the Floating Catchment Area (FCA) technique is used. The calculations from the FCA produce a Spatial Accessibility Index (SPAI) that increases as: the supply of veterinary care increases; the distance or travel time between neighbourhoods and practices decreases; and the demand for care in the neighbourhood decreases. A high SPAI indicates better accessibility for the neighbourhood.

Given these features of the SPAI three pieces of information are needed: the location and number of veterinary surgeons; the travel time between neighbourhoods and veterinary practices; and the location and number of pets in each neighbourhood. The first piece of information is provided to us by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons through their ‘find a vet’ web site data base. The car journey times are calculated using a routing algorithm that uses the open street map network. The final piece is the number of pets in each neighbourhood, and this presents a challenge since there are no up to date counts of the pet population at the scale of such neighbourhoods. As a result, we have produced our own estimates.

Estimating the Pet Population

We used the small area estimation technique of spatial microsimulation to obtain estimates of the number of pet owning households in each Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) in England and Wales (there are roughly 700 households in each LSOA). For this to take place, firstly information is needed on how many households with various characteristics (e.g. property type; tenure; size) there are in each LSOA, and these can be obtained from the 2021 Census of England and Wales. Secondly a data set of individual households is needed that contains all these same characteristics and also the measure we are estimating, here whether a household owns at least one pet. The data we used for this purpose was a consumer lifestyle data obtained from the Geographic Data Service.

Spatial microsimulation works by ‘cloning’ households in the individual data so they match the characteristics of the properties in the area. These cloned households then provide for each LSOA a count of the number of households in the LSOA who own at least one pet. Using these estimates we see that the proportion of pet owning households was highest in more rural locations (with approximately 70% of households owning at least one pet) and lowest in multi-cultural and inner city location (around 45% of households). The level of pet ownership did not appear to vary much by deprivation though, with a constant 60% of household owning at least one pet. Other recent surveys have suggested that nationally around 60% of UK households own at least one pet.

Variations in the Spatial Accessibility Index

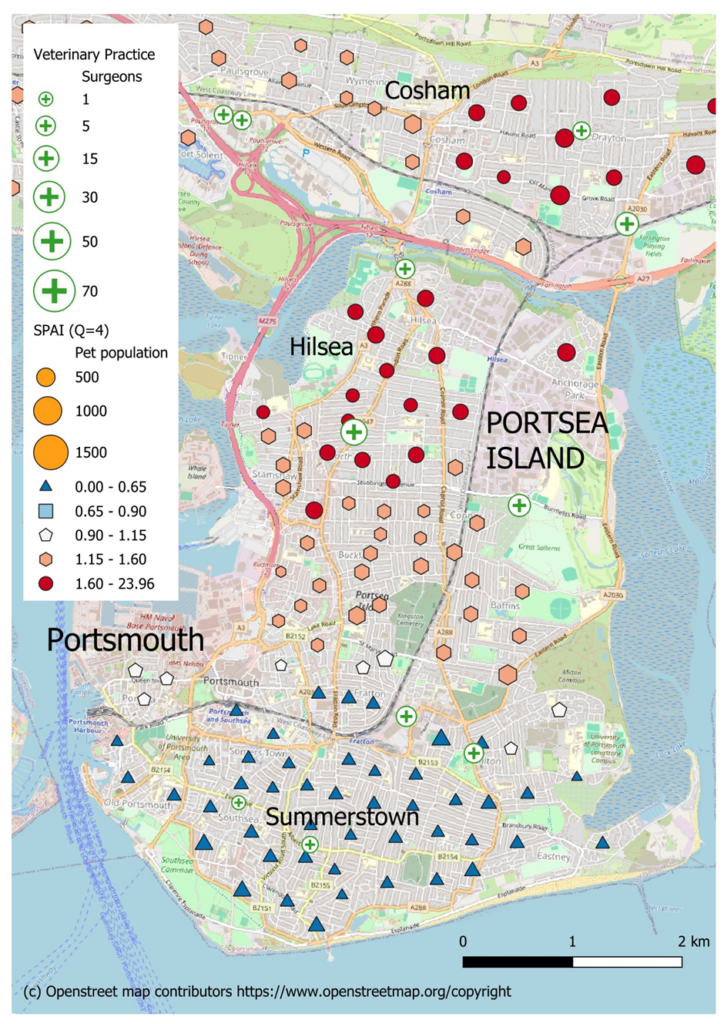

Now that we have the three elements needed for the calculation of the SPAI we can perform the necessary calculations. In the article we showed how the SPAI varies by the population characteristics of the neighbourhood, its level of deprivation and its urban/rural nature. A case study showing how the SPAI varied in and around the town of Barnsley in South Yorkshire was also presented. Here we will present another case study, Portsea Island in southern England and also identify an extensive potential veterinary desert in east London.

Portsea Island

Portsea Island is an island off the south coast of England and contains the city of Portsmouth and a historically significant naval base. The fact that Portsea is an island impacts greatly on the SPAI. The values of the SPAI are lowest towards the south of the island in Summerstown. Whilst Summerstown has 3 modest sized practices, and two small practices these are thinly spread to serve the pet population of the area.

Whilst there is more substantive veterinary provision toward the north of the island (in Hillsea) and on the mainland (in Cosham), these are at some distance away and are in heavy demand from the pet population in their area. Hillsea in the north of the Island does well, with high SPAI values, having access to three practices, with one a large practice of 17 surgeons in total, and additionally good road links to practices on the mainland.

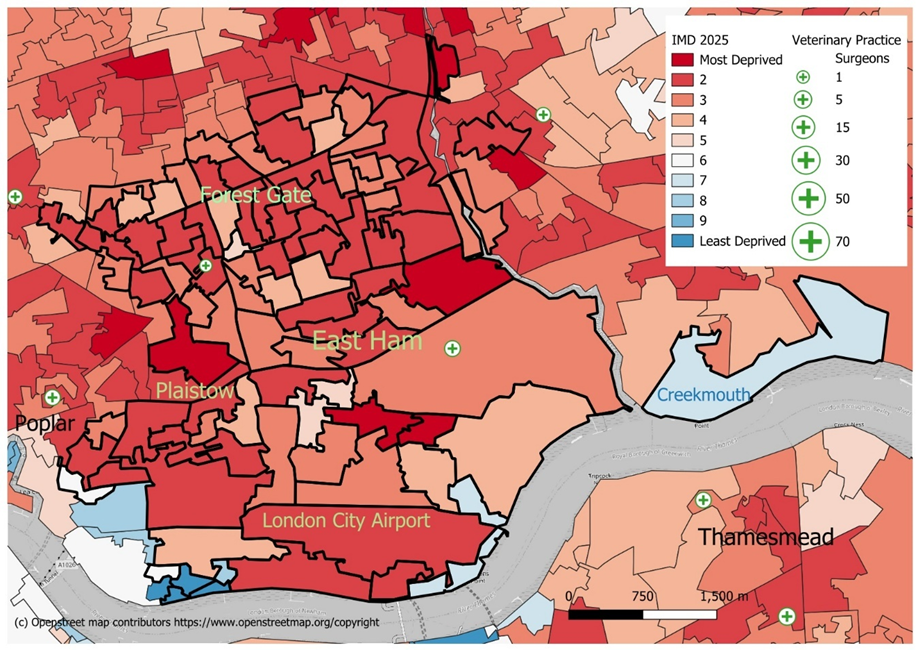

East London

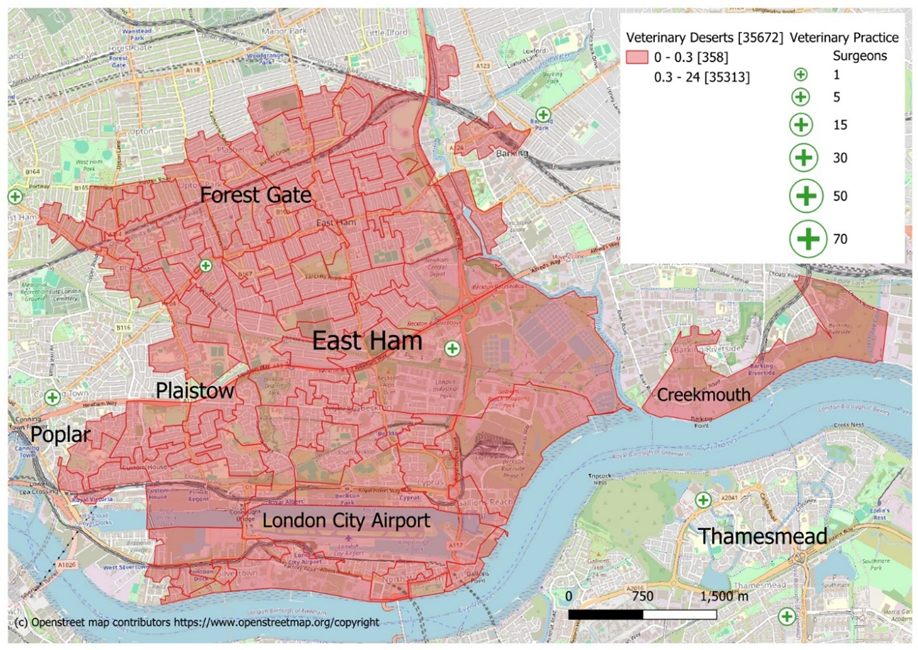

If we identify the 1% of LSOAs with the lowest SPAI then we can begin to identify potential veterinary deserts. When we do this we see a particular concentration in the east end of London, around East Ham. This is a (largely) continuous cluster of LSOAs with poor access to veterinary care, with just a few practices and each of these with a small number of surgeons available to serve the pet population for such a large area.

We can also see how deprived these neighbourhoods are by looking at their 2025 Index of Multiple deprivation. Many are in the top two most deprived deciles nationally. These neighbourhoods are therefore double challenged in terms of accessing veterinary care, few practices located locally and few financial resources to pay for any necessary care.

How do we improve access to veterinary services?

Much as food banks are set up in locations where access to food is difficult through poor access to food shops or people simply being unable to afford to buy food, there is an identifiable case here to encourage pet charities such as the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) to set up or expand clinics in such locations. Other alternative solutions are the greater use of telecare so that owners can remotely access care for their pets or mobile veterinary services where vets visit pet owners in their own home.

Find out more

Read the full paper in the Animal Welfare Journal: Measuring the accessibility of veterinary care for companion animals in England and Wales

With thanks to Dr Stephen Clark, Prof Graham Clarke, Prof Nik Lomax and Dr Will James for their contribution to this article.